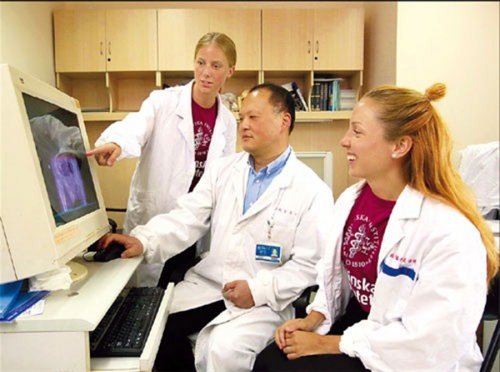

Hanna Lovbrand (right) and Diana Sylwander from Sweden work with

a Chinese doctor in Ruijin Hospital. The Swedes are in the city on

an medical exchange program. Shanghai health authorities are using

the exchanges to collect ideas on how to improve medical care. —

Wang Rongjiang

FOREIGN medical students on exchange programs in China are often

taken aback by practices here that contrast sharply with those back

home.

Like the absence of family doctors as gatekeepers to specialists.

Like clinic doors left open, allowing sundry people to wander in

and out while a doctor is seeing a patient.

When people need a doctor in China, they normally go to local

hospitals, which are usually crowded. Foreigners are amazed at the

workload Chinese doctors bear.

“Chinese doctors work so quickly,” said Hanna Lovbrand, a senior

medical student from Karolinska Institutet in Sweden. “They have to

make decisions within minutes because they treat so many patients a

day. In my country, by contrast, a doctor always talks with the

patient for about 20 minutes.”

She and fellow Swede Diana Sylwander are in Shanghai for a

10-week exchange program with Shanghai Jiao Tong University’s

School of Medicine. At Ruijin Hospital, one of the city’s leading

public health facilities, they have rotated through three

departments to view medical practices.

“We are interested in learning about the Chinese healthcare

system, Chinese medical practices and traditional Chinese

medicine,” Lovbrand said.

There are an increasing number of exchange programs being

initiated in Shanghai to foster sharing of information and

experiences between the city’s healthcare system and those of

foreign countries. The exchanges bring foreign medical students

here and send Chinese medical students abroad.

Lovbrand said she and Sylwander found that Ruijin Hospital’s

operating theaters, medical equipment and basic surgical procedures

are similar to those of Western countries. What is different is the

doctor-patient relationship, she said.

“What interests us is how Chinese patients know which specialists

to go to for their ailments,” Lovbrand said. “In Sweden, we must

first visit a family doctor, who then refers us to appropriate

specialists.”

Shanghai health authorities are using the exchanges to collect

ideas on how to improve medical care here.

“We are pushing cooperation with Western counterparts,” said Gao

Hong, an official of Jiao Tong’s School of Medicine who oversees

exchange programs. “It will help the young Chinese medical

professionals to learn from countries with more developed

healthcare systems. For example, our medical students can learn

about respect for patient privacy.”

It’s not only foreign students coming to China who benefit from

exchanges. Chinese medical students going abroad also come back

with experiences that shape their professional attitudes.

Dong Liang, a senior medical student at Jiao Tong, said he was

surprised by the practices he saw on a two-month exchange program

in Canada. While there, he was assigned to the internal medicine

department at Toronto General Hospital and also visited general

practice clinics in the city.

“In a Western hospital, a doctor is only part of the medical

team,” Dong said. “The team also includes nurses, social workers,

therapists and a patient’s family doctor. They receive daily

briefings on a patient’s condition and handle all related care,

such as rehabilitation and psychological support. Patients there

have a better recovery rate. We don’t have such a system in China.”

Chinese medical students are also surprised to see the respect to

patients and their privacy, he said. “It is prohibited there to

take photos or print out a patient’s record,” Dong said. “Doctors

can’t check the information on patients not under their care. All

these practices are unheard of in China.”

Dong said he would like to see China’s healthcare system develop

a frontline of primary care, which means general practitioners

seeing patients before specialists. That would ease the workload of

big hospitals and deliver better health care, he said. “Though

Shanghai has started to promote use of general physicians, the

training and promotion of family doctors lags behind the medical

systems of the West,” he said.

Jiao Tong’s School of Medicine is collaborating with the

University of Ottawa in Canada to establish a joint medical school

aimed at providing global physician education.

Jacques Bradwejn, dean of the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of

Medicine, said family medicine will be an important segment of the

joint program. “Family medicine is well developed in the United

States, Canada and many Western countries,” he said. “People get

primary care in their local communities, and the same family doctor

follows a person’s health track for a long time. We will train

Chinese medical students in family medicine, and we hope it will

provide a demonstration platform for Shanghai and China.”